Exploring the History of Emotions

The history of emotions grew as an academic field as it revealed a new way to research history from its previously political approach. Historians have since proved that “emotions have larger social and political implications and can shape public realities”[1], and scholars have removed their focus from how people visibly behave to what prompted their specific reactions and behaviours. Through explorations of “the anger, the envy, the love, and the greed”[2]

of their historical subjects, and attempting to reveal what is going on inside their heads, historians have been able to develop previously “impoverished explanations of human motivation”[3] and refine historical theory. Emotions define every aspect of human life; they shape how we earn a living, live with each other as families, identify ourselves, express ourselves politically and have faith. Human emotions are not static, they change over time in the form of emotional shifts, and thus academics across multiple fields like anthropology and psychology have agreed that “emotions have both biological and cultural components and that societies influence the expression, repression and meaning of feelings”[4] by naming them and assigning different values to different emotions.

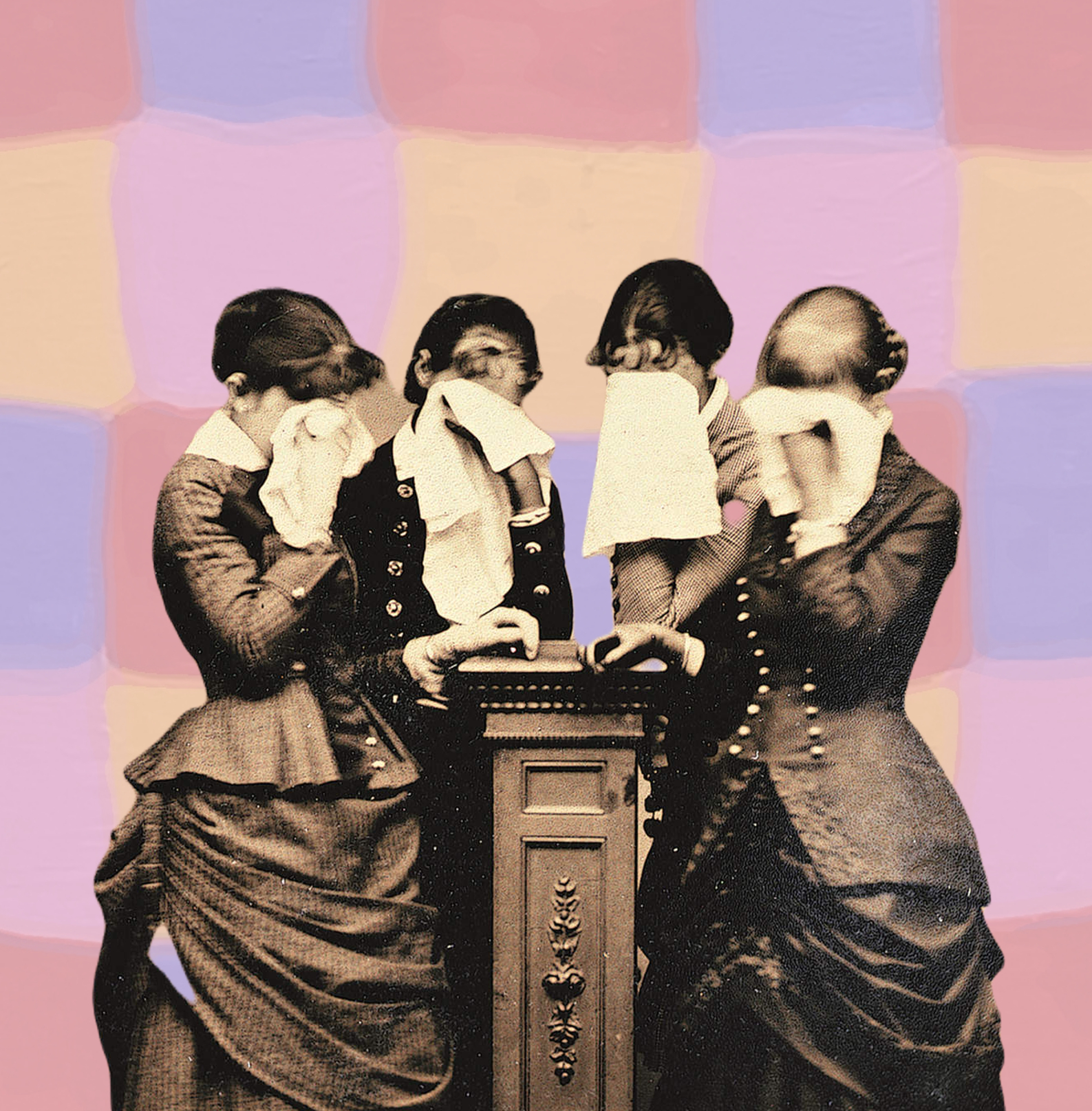

Peter and Carol Stearns coined the term ‘emotionology’ to describe “the attitudes or standards that a society, or a definable group within a society, maintains toward basic emotions and their appropriate expression”[5], and attempted in their studies to discover why certain emotions are disparaged or encouraged within society whilst others are left unbothered. They note how young girls in the nineteenth century felt anger more frequently than contemporary women, but their anger was criticised more and was, therefore, “concealed within family disputes”[6], or else they would be represented as hysterical. In comparison, younger boys in the nineteenth century were almost praised for expressing anger, as “a boy’s temperament [was] much more predictive of adult personality”.[7] Through focusing on emotionology, historians are able to produce a wide variety of works on all emotions whilst exploring “how social norms about emotional expression changed in reaction to transformations in family life and law, economic growth, and political upheaval”.[8]

Whilst understanding that emotions change over time, historians are able to study standard emotions and supplement them with in depth investigations of how individuals “coped with, expressed, and repressed their feelings, sometimes following, sometimes flouting social norms”.[9]

For example, in the Victorian era there was a rise in emotional repression as there was a separation between men at work versus women in the domestic sphere. This separation led to “new emotional differentiation, in ideal types, between men and women”[10], whereby the female ideal was quiet demure femininity in comparison to the aggressive independence of males. Women were seen to be emotional and irrational beings in comparison to men, which in turn influenced the fact that women were not allowed to vote in politics. Monique Scheer encapsulates this in her analysis that “boys are specifically told not to cry, girls to swallow their anger”.[11] However, as women grew to ignore the social and emotional conventions that were placed upon them, feminist movements rose to counter them as an act of political defiance, which was further denounced as emotional and irrational behaviour by a patriarchal society. Emotions in social contexts have historically been linked with irrationality by historians; Charles Tilly, for example, views emotion as “an irrelevant by-product of protest, whose contours are firmly determined by organisational potential and rational crowd goals”.[12]

However, Rob Boddice states that movements of social protest, from marches and strikes to riots and rebellions, are a “rational or intentional set of decisions and strategic moves, with the aim of attaining preconceived targets”.[13]

As the field of emotions studies has progressed, historians have discovered that there are a multitude of emotional standards within a society rather than a single emotional convention, sometimes with differing conclusions. Barbara Rosenwein, a scholar of medieval history, has suggested that there are emotional communities that exist within all societies that enable emotional expression.[14] Rosenwein proposes that “that in the course of a day, individuals may move through a range of them—from churches to taverns to parlours—each of which require different affective styles”.[15] William Reddy has offered an alternative approach during his study of eighteenth century political culture in France. Reddy explores the idea of emotional regimes and refuges within society, where the emotional regime acts to “spread and enforce dominant emotional norms”[16] and the emotional refuge acts as a shelter from such regimes, where individuals seek emotional freedom. Despite some conflicting ideas of emotions within society, historians are able to agree that “while there may be some basic emotions that exist in all people, how they are expressed and what they mean varies dramatically across cultures and centuries”.[17]

Since history as a discipline “has never quite lost its attraction to hard, rational things”[18], the study of emotions has remained on the peripherals of the field and its methodologies have been criticised for going against conventional historical practice. Exploring the history of emotions is difficult as there is no set record of how people felt throughout history. Some historians have turned to “advice guides, sermons, editorials, child-rearing manuals, and other forms of prescriptive literature that offered instructions on how and when to display or suppress emotions”[19], whilst others rely on personal diaries, letters and literature when attempting to reveal emotional pasts. However, all sources in the field have limitations; “they reveal much about how artists, writers, psychologists, and manners experts understood the world, but they cannot reveal whether such views and sentiments were widely shared.”[20] Nevertheless, Jan Plamper believes that such limits “are little different to those encountered in other historical subdisciplines”.[21]

The Stearns have discussed the problems and limitations of enquiring into emotional history, as “such studies could not capture actual experience, nor could they describe the perceptions of those outside the literate culture that consumed such advice”.[22] The emotions experienced by historic individuals have disappeared, but traces of those emotions remain through symbols and words left behind. Whilst these “are not the same as emotions, […] they bear a relation to them” [23] despite that uncertain relation taking time to decipher. Language and the written word are imperative sources when exploring the history of emotions, as verbal expressions “are themselves instruments for directly changing, building, hiding, [and] intensifying emotions”.[24] Starobinski has furthered this view, by concluding that “the history of emotions […] cannot be anything other than the history of those words in which the emotion is expressed.”[25] When exploring such written sources, historians must be aware that they risk imposing their modern views of emotions onto periods that may have viewed emotions differently. Nevertheless, Peter and Carol Stearns have suggested that despite such limitations, studying emotions can allow us to explore how individuals throughout history either conformed to or diverged from their contemporary social conventions.

Further reading:

Åhäll, Linda. “Affect as Methodology: Feminism and the Politics of Emotion.” International Political Sociology 12 (2018): 36-52.

Boddice, Rob. The History of Emotions. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018.

Dyhouse, Carol. Girl Trouble: Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2014.

Hercus, Cheryl. “Identity, Emotion and Feminist Collective Action.” Gender and Society 13, no. 1 (1999): 34-55.

Lutz, Catherine. “Emotions and Feminist Theories.” In Gender Feelings, edited by Daniela Rippl and Verena Mayer, 104-121. Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2008.

Matt, Susan J. “Recovering the Invisible: Methods for the Historical Study of the Emotions.” In Doing Emotions History, edited by Peter N. Stearns and Susan J. Matt, 41-53. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Plamper, Jan. The History of Emotions: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Reddy, William M. “Against Constructionism: The Historical Ethnography of Emotions.” Current Anthropology 38, no. 3 (1997): 327-351.

Rosenwein, Barbara H. “Problems and Methods in the History of Emotions.” Passions in Context: International Journal for the History and Theory of Emotions 2 (2011): 1-32.

Scheer, Monique. “Are Emotions a Kind of Practice (And Is That What Makes Them Have a History)? A Bourdieuian Approach to Understanding Emotion.” History and Theory 51 (2012): 193-220.

Stearns, Peter N., and Carol Z. Stearns. “Emotionology: Clarifying the History of Emotions and Emotional Standards.” The American Historical Review 90, no. 4 (1985): 813-836.

Stearns, Peter N., and Matt, Susan J., ed. Doing Emotions History. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

References:

[1] Peter N. Stearns and Susan J. Matt, ed., Doing Emotions History (University of Illinois Press, 2014), 1.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Stearns and Matt, Doing Emotions History, 2.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Peter N. Stearns and Carol Z. Stearns, “Emotionology: Clarifying the History of Emotions and Emotional Standards,” The American Historical Review 90, no. 4 (1985): 813.

[6] Stearns and Stearns, “Emotionology,” 827.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Stearns and Matt, Doing Emotions History, 4.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Stearns and Stearns, “Emotionology,” 820.

[11] Monique Scheer, “Are Emotions a Kind of Practice (And Is That What Makes Them Have a History)? A Bourdieuian Approach to Understanding Emotion,” History and Theory 51 (2012): 216.

[12] Stearns and Stearns, “Emotionology,” 817.

[13] Rob Boddice, The History of Emotions (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), 60.

[14] Barbara H. Rosenwein, “Problems and Methods in the History of Emotions,” Passions in Context: International Journal for the History and Theory of Emotions 2 (2011): 1.

[15] Stearns and Matt, Doing Emotions History, 8.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Stearns and Matt, Doing Emotions History, 9.

[18] Stearns and Matt, Doing Emotions History, 1.

[19] Stearns and Matt, Doing Emotions History, 4.

[20] Susan J. Matt, “Recovering the Invisible: Methods for the Historical Study of the Emotions,” in Doing Emotions History, ed. Peter N. Stearns and Susan J. Matt (University of Illinois Press, 2014), 49.

[21] Jan Plamper, The History of Emotions: An Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2015), 33.

[22] Stearns and Matt, Doing Emotions History, 4.

[23] Matt, “Recovering the Invisible,” 42.

[24] William M. Reddy, “Against Constructionism: The Historical Ethnography of Emotions,” Current Anthropology 38, no. 3 (1997): 331.

[25] Matt, “Recovering the Invisible,” 43.

0 Comments Add a Comment?