Why did the Vikings Decide to Raid?

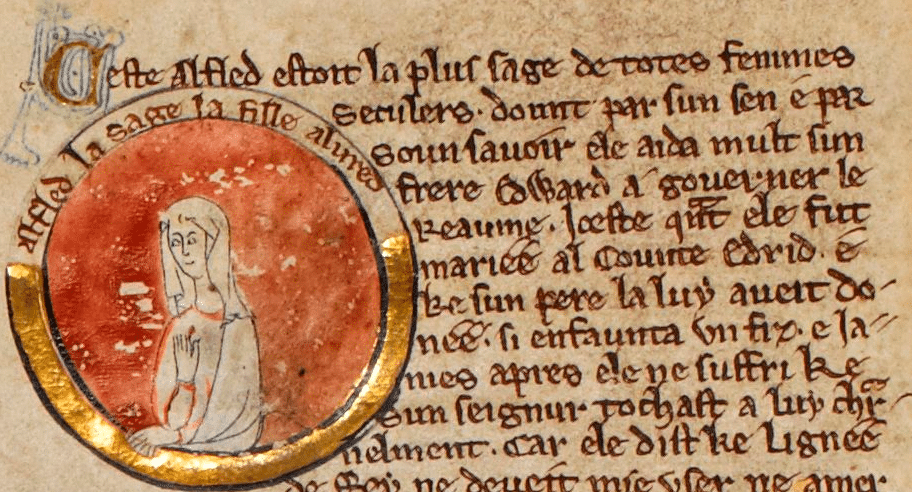

Anglo-Saxon ChroniclesThe precise causes behind the Viking raids are, for the most part, unknown; the Vikings as a people had pagan beliefs, which meant that they left behind no written sources to explain their actions. The only evidence of their raiding came from those they raided; the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles depicted the Vikings as savages who invaded and pillaged churches and coastal towns. The Chronicles provide us with the effects of Viking raiding, but the causes behind them remain somewhat unclear. They also provide us with a biased account “exaggerated by ecclesiastical outrage and pious shock”[1], so the few accounts of Viking raiding available have to be read with caution. Historians have devised several explanations for Viking raiding, which include social pressures in Scandinavia and environmental conditions, as well as various push, pull and enabling factors. However, historians only see the effects of the raiding through hindsight, and sometimes fail to realise that people at the time may not have known the true reason behind Viking migration, let alone the full effects of their actions. The reason behind their arrival, and eventual migration and settlement, will never have a satisfactory explanation, however, scholars have proposed myriad reasons as to why the Vikings may have left Scandinavia.

Anglo-Saxon ChroniclesThe precise causes behind the Viking raids are, for the most part, unknown; the Vikings as a people had pagan beliefs, which meant that they left behind no written sources to explain their actions. The only evidence of their raiding came from those they raided; the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles depicted the Vikings as savages who invaded and pillaged churches and coastal towns. The Chronicles provide us with the effects of Viking raiding, but the causes behind them remain somewhat unclear. They also provide us with a biased account “exaggerated by ecclesiastical outrage and pious shock”[1], so the few accounts of Viking raiding available have to be read with caution. Historians have devised several explanations for Viking raiding, which include social pressures in Scandinavia and environmental conditions, as well as various push, pull and enabling factors. However, historians only see the effects of the raiding through hindsight, and sometimes fail to realise that people at the time may not have known the true reason behind Viking migration, let alone the full effects of their actions. The reason behind their arrival, and eventual migration and settlement, will never have a satisfactory explanation, however, scholars have proposed myriad reasons as to why the Vikings may have left Scandinavia.Social pressures within Scandinavia may well have pushed the Vikings to leave and discover new lands. The typical explanation for the diaspora of a people was an expanding home population. Population pressures would have forced the Vikings to leave Scandinavia, as worries about food production and overcrowding usually spurred the need for expansion. However, recent studies demonstrate little to no change in Viking populations, as there is no clear indication to show an increased birth rate; there were no drastic surges in burials, and settlement patterns remained stable. Näsman claims that “when the Danes started to settle in the West, there was still room left for a considerable population growth in Denmark”.[2] Therefore, it is highly unlikely that population pressure was the main factor behind the increase of Viking raids.

Pressures placed on males to find a wife has also been put forward as a reason for Vikings to raid. Some historians believe that there was a “male youth bulge”[3]; an imbalance of the sexes caused by female infanticide, as with fewer women around to marry, high prices would have had to be paid for dowries. As the richer men were obtaining all of the eligible women, many men from lower statuses had to be willing to risk their lives during raids to be able to afford a wife.[4] Ben Raffield et al. theorise that Viking males practiced “polygyny and concubinage”[5], allowing them to have several wives and “having sexual relations and often cohabiting without being recognised as husband and wife”.[6] Raiding would have provided the Vikings with a quick way to acquire the money needed to pay for a bride, instead of having to work for a long time to raise an adequate amount of money to wed. Raffield also claims that the want or need of a wife “increased male-male competition, and thus in turn led to a volatile socio-political environment in which men sought to distinguish themselves by obtaining wealth, status, and female slaves”[7], which in turn spurred the beginning of intense Viking activity. However, this ‘youth bulge’ theory also has holes in it; there has been no evidence of increased female burials or explanations as to why female infanticide existed in Viking culture. James H. Barrett theorises that a possibility for female infanticide is that “increasingly militaristic competition associated with Scandinavian state formation”[8] which “led to a preference for sons over daughters”[9], but there is no evidence to back this up.

Another theory behind what caused the Viking diaspora is social pressures influenced by the political atmosphere at the time, both internally in Scandinavia and externally in Europe. James H. Barrett states that this is “one of the most long-standing and most convincing ingredients in the Viking Age recipe”.[10] The Carolingian Empire, directly to the south of Scandinavia, possessed both large armies and a desire to expand and conquer Europe, so some historians believe that the Vikings raided and attacked as defensive measures. Proof that there was a threat from the Carolingians exists as the Vikings constructed the Danevirke earthwork in the early to mid 700s, which protected Hedeby, an important Viking trading centre, from Carolingian capture.[11] However, the Danevirke was built a long time before the Vikings began raiding the Carolingian Empire, and this theory gives no explanation as to why the Vikings would branch out and raid the British Isles. Carolingian threats may have had an impact on internal politics; with the risk of invasion, smaller kingdoms within Scandinavia were pressured to form together and join forces for protection. As states became larger, perhaps more wealth was needed in order to function, which would have influenced Viking raiding. This “centralisation of power”[12] within Scandinavian kingdoms is also seen to be due to the “partly ficticious unification of Norway under Harald Fairhair”[13], where Harald made an oath to the woman he wanted to marry that he wouldn’t cut his hair until Norway was conquered and united. It is presumed that those who did not wish to be conquered and united would join expeditions of raiders and move overseas. Furthermore, if the smaller states were all working together peacefully, it is feasible to assume that the Vikings craved conflict, as there were now no internal conflicts between the Vikings themselves and they had a reputation for having a strong military culture. However, at the time when the Carolingians posed a threat to the Vikings, state formation was only in its earliest stages; most state formation would occur much later. This strong military culture that the Vikings possessed has also been used as a possible reason as to why the Vikings began raiding overseas; societal pressures were placed on males to have great military prowess, and with their high quality weapons they were expected to be warriors seeking glory and to bring home plunder. Scandinavian ideologies must have held a heavy precedent during the Viking Age; raiding was a high risk and high gain activity that many would not return from, due to anything from shipwreck and falling in battle to dying of disease.[14] To willingly raid meant risking your life, and without “deeply seated views in duty and predestination”[15] many would not have left Scandinavia. Price provides us with a valuable insight into why Vikings were willing to risk their lives; the Vikings believed in the “pre-ordained and permanent ruin of all creation and the powers that shaped it, with no lasting afterlife for anyone at all”.[16] With this mentality and belief in ‘Ragnarok’, it did not matter what the Vikings did during their lives, as their fate was already predetermined.[17] In addition to this, Stephen P. Ashby believes that “elites have long held the ability to garner power and prestige by reference to places of the ‘Other’”.[18] The unknown is said to hold “great power, by virtue of its very mystery”[19], which was seen to provide those who conquered new lands and discovered new commodities with “a certain political and ideological legitimacy”.[20] However, some historians disagree that this was a necessary cause of Viking raiding; many other contemporary groups other than the Vikings placed the same social expectations on their males, and owned the same technologically advanced weapons. Furthermore, evidence exists of military adventuring earlier than the Viking age.

Harald Fairhair

Harald Fairhair

Conflicts of ideology between Pagans and Christians may have induced social pressures in Scandinavia that tempted the Vikings to raid overseas. As Christian missionary movements were increasingly popular in Continental Europe from the early 7th century, the Vikings, as believers in Paganism, may have felt that there was a threat to their belief system, which may have prompted their raiding. Christianity was a new, unfamiliar religion to the Vikings; there may possibly have been Christian influences in Scandinavia before the Vikings began raiding, but there was no evidence to show that they were threatened by Christianity. There was also no indication that raiding was backed with religious motivation; whilst accounts of raids written by those raided believed that the “heathens” were attacking Christianity, there is no evidence showing that that was the actual case from the perspective of the Vikings. Christians in Britain at the time of the raids believed them to be a reckoning from God for their sins[21], as the Vikings usually targeted coastal towns and their churches. The churches and monasteries of the British Isles were pull factors in themselves for the Vikings; ecclesiastical centres of wealth contained portable goods that were easy for the Vikings to take back to Scandinavia, such as shrines, book covers and crosses made of expensive metals.[22] As well as tradable goods, monasteries also provided Vikings with an opportunity to target and kidnap people to sell as slaves, as the areas surrounding them had populations that were well distributed, and contained animals and land for farming and produce growth. This theory is a valid explanation as to why these specific, ecclesiastical areas were raided, however, it fails to provide a reason as to why Vikings raided at all. They would not have realised the vast wealth that churches contained until they had already left Scandinavia and raided coastal towns.

The Vikings were able to establish an expansive trading network during the 7th and 8th centuries around the North Sea, as they saw the opportunity to export surplus exotic goods acquired by elites. This would be a pull factor for the Vikings, and encourage them to continue obtaining goods in order to trade and generate more wealth. Early trade conducted by the Vikings would have shown them that “a large part of the world lay undefended, presenting opportunities for power and glory, gold, adventure, new lands”.[23] Viking trading shows that they were aware of centres of wealth in Europe, as well as their political systems and the capacity of their militaries. For these reasons, trading would further encourage raiding as the Vikings would have identified which areas would be more beneficial to raid, due to the geography and ease of access. However, some historians argue that the trading system already in place was working well enough; the Vikings should have had no reason to further raid.

After running through some of the social pressures that may have induced Viking raiding, I am now going to explore some of the environmental conditions that may have pushed them out of Scandinavia in the search for better living conditions. Some historians believe climatic change may have been a pull factor as to why the Vikings left their home shores; palaeo-environmental studies show that there was a “Medieval Warm Period”[24], where the climate became hotter towards the end of the 1st millennium AD. A temperature increase would have meant that areas previously uninhabitable might become agriculturally affluent. As Norway was full of large fjords and coastlines, there would have been no agricultural development for the growing Viking population, so they may have been seeking hospitable lands through raiding and exploration. However, James H. Barratt argues that the Medieval Warming Period may have never existed in the first place[25], and more recent climatic studies show that there was very little, or no change in the climate over the Viking era, and climate change would be a cause for settlement, not raiding.

Further explanation for Viking raiding comes from the demand from beyond Scandinavia for resources. Stephen P. Ashby believes that “it is likely that awareness of European trade and the diverse, weathy kingdoms it connected exerted some pull on Scandinavian aristocracies”.[26] Exploration to eastern lands led the Vikings to new trading networks and connections; slaves were desperately wanted in the Arab world, as well as northern products like fur, and the Vikings were rewarded with vast quantities of silver in return for them.[27] This could provide us with an explanation as to why the Vikings raided villages and stole people away, but trading in the east only began in the 10th century; therefore, this theory does not explain the cause of Viking raiding earlier in the 8th century. Furthermore, whilst these trade routes would undoubtedly encourage “mercantile and military operations in the east”[28], it does not provide us with any answers as to why the Vikings would travel to the west.

The development of “naval technology and seafaring knowledge”[29] is seen to be one of the most common explanations as to why the Vikings expanded to overseas countries. The Vikings had supremely effective long-ships with square sails, which allowed them to travel further and easier.[30] If they had the means to explore and raid, it would give them the motivation to leave Scandinavia in order to acquire more wealth. It was a dangerous feat, but worth it for the glory of conquering an area and bringing home their plunder. The Vikings also possessed effective navigational tools, such as sun dials, crystals to use in cloudy weather, and the knowledge of how to use stars and birds flying to roost to help them to navigate the seas.[31] However, historians have provided evidence from traded goods that large quantities of people were moving across the North Sea from as early as the 4th century, and there was no documented change in Viking shipbuilding from the mid 8th century onwards. They argue that there may have been advances in seafaring to utilise existing technology, but this is unproven. James H. Barrett argues that technological developments were not necessarily a cause of Viking raiding, but an essential condition, and that “large-scale seaborne raiding, conquest and/or migration could have emanated from Scandinavia long before, thus reducing the causative power of Viking ships”.[32] Therefore, for “reasons of chronology and logic, the development of maritime technology cannot be said to have caused the Viking Age, even if it was a prerequisite for extended sea voyages”.[33]

In conclusion, there is no set cause as to why the Vikings left Scandinavia and raided foreign lands, and many different historians argue and favour different causes. In order to fully explain the motives of the Vikings you must consider different “activities of different periods”[34], as well as the “significant regional variation both in the character of and the reasons behind the so-called Viking expansion”.[35] If deciding between societal pressures and environmental conditions, I believe that social pressures placed on the Vikings better explain increased Viking raiding, however, all theories viewed in this essay contain their own downfalls and uncertainties. Ultimately, raiding represented a “mutually beneficial means of achieving social advancement, success in the marriage market, and, for elite men, political power”.[36] The Norse men had their own wants and desires that caused them to raid, and were “prepared to make demands and had the will, strength and technical means to enforce them”.[37] Whether they craved lands to farm, infamy and power, or the funds to obtain a wife, “trade, colonisation, piracy, and war would get them these things and such could be practised only at the expense of neighbours, near and far”.[38]

Further Reading:

Ashby, S. P., ‘What really caused the Viking Age? The social content of raiding and exploration’, Archaeological Dialogues, 22 (1), (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.86-106

Barrett, J. H., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’, Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008), p.671-685

Graham-Campbell, J., The Viking World, (Frances Lincoln Ltd, 2013), p.42-57

Jones, G., A History of the Vikings, (Oxford University Press, 1984), p.182-204

Magnusson, M., Viking Expansion Westwards, (The Bodley Head Ltd, 1973), p.17-41

Näsman, U., ‘Raids, Migrations, and Kingdoms – the Danish Case’, Acta Archaeologica (vol. 71, 2000) p.1-7

Price, N., The Viking way: religion and war in late Iron Age Scandinavia (AUN 31), (Upsala 2002), p.263-75

Raffield, B., Price, N., and Collard, M., ‘Male-biased operational sex ratios and the Viking phenomenon: an evolutionary anthropological perspective on Late Iron Age Scandinavian raiding’, Evolution and Human Behaviour (38), (Elsevier 2017) p.315-324

Roesdahl, E. and Wilson, D. M., From Viking to Crusader. The Scandinavians and Europe 800-1200, (Copenhagan 1992), p.24-29

Sawyer, P. H., ‘The Causes of the Viking Age’, The Vikings (edited by Rarrell, R. T.), (Phillimore, 1982) p.1-7

References:

[1] Magnusson, M., Viking Expansion Westwards, (The Bodley Head Ltd, 1973), p.19

[2] Näsman, U., ‘Raids, Migrations, and Kingdoms – the Danish Case’, Acta Archaeologica (vol. 71, 2000) p.3

[3] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.677

[4] Raffield, B., Price, N., and Collard, M., ‘Male-biased operational sex ratios and the Viking phenomenon: an evolutionary anthropological perspective on Late Iron Age Scandinavian raiding’, Evolution and Human Behaviour (38), (Elsevier 2017) p.322

[5] Raffield, B., Price, N., and Collard, M., ‘Male-biased operational sex ratios and the Viking phenomenon: an evolutionary anthropological perspective on Late Iron Age Scandinavian raiding’, Evolution and Human Behaviour (38), (Elsevier 2017) p.315

[6] Raffield, B., Price, N., and Collard, M., ‘Male-biased operational sex ratios and the Viking phenomenon: an evolutionary anthropological perspective on Late Iron Age Scandinavian raiding’, Evolution and Human Behaviour (38), (Elsevier 2017) p.315

[7] Raffield, B., Price, N., and Collard, M., ‘Male-biased operational sex ratios and the Viking phenomenon: an evolutionary anthropological perspective on Late Iron Age Scandinavian raiding’, Evolution and Human Behaviour (38), (Elsevier 2017) p.316

[8] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.677

[9] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.677

[10] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.678

[11] Näsman, U., ‘Raids, Migrations, and Kingdoms – the Danish Case’, Acta Archaeologica (vol. 71, 2000) p.4

[12] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.678

[13] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.678

[14] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.680

[15] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.680

[16] Price, N., The Viking way: religion and war in late Iron Age Scandinavia (AUN 31), (Upsala 2002)

[17] Price, N., The Viking way: religion and war in late Iron Age Scandinavia (AUN 31), (Upsala 2002)

[18] Ashby, S. P., ‘What really caused the Viking Age? The social content of raiding and exploration’, Archaeological Dialogues, 22 (1), (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.94

[19] Ashby, S. P., ‘What really caused the Viking Age? The social content of raiding and exploration’, Archaeological Dialogues, 22 (1), (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.94

[20] Ashby, S. P., ‘What really caused the Viking Age? The social content of raiding and exploration’, Archaeological Dialogues, 22 (1), (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.94

[21] Sawyer, P. H., ‘The Causes of the Viking Age’, The Vikings (edited by Rarrell, R. T.), (Phillimore, 1982) p.1

[22] Ashby, S. P., ‘What really caused the Viking Age? The social content of raiding and exploration’, Archaeological Dialogues, 22 (1), (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.91

[23] Roesdahl, E. and Wilson, D. M., From Viking to Crusader. The Scandinavians and Europe 800-1200, (Copenhagan 1992)

[24] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.673

[25] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.673

[26] Ashby, S. P., ‘What really caused the Viking Age? The social content of raiding and exploration’, Archaeological Dialogues, 22 (1), (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.91

[27] Ashby, S. P., ‘What really caused the Viking Age? The social content of raiding and exploration’, Archaeological Dialogues, 22 (1), (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.91

[28] Ashby, S. P., ‘What really caused the Viking Age? The social content of raiding and exploration’, Archaeological Dialogues, 22 (1), (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.91

[29] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.671

[30] Graham-Campbell, J., The Viking World, (Frances Lincoln Ltd, 2013), p.43

[31] Graham-Campbell, J., The Viking World, (Frances Lincoln Ltd, 2013), p.55

[32] Barrett, J., ‘What caused the Viking Age?’ Antiquity, 82 (317), (2008) p.673

[33] Ashby, S. P., ‘What really caused the Viking Age? The social content of raiding and exploration’, Archaeological Dialogues, 22 (1), (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p.90

[34] Näsman, U., ‘Raids, Migrations, and Kingdoms – the Danish Case’, Acta Archaeologica (vol. 71, 2000) p.1

[35] Näsman, U., ‘Raids, Migrations, and Kingdoms – the Danish Case’, Acta Archaeologica (vol. 71, 2000) p.1

[36] Raffield, B., Price, N., and Collard, M., ‘Male-biased operational sex ratios and the Viking phenomenon: an evolutionary anthropological perspective on Late Iron Age Scandinavian raiding’, Evolution and Human Behaviour (38), (Elsevier 2017) p.322

[37] Jones, G., A History of the Vikings, (Oxford University Press, 1984), p.196

[38] Jones, G., A History of the Vikings, (Oxford University Press, 1984), p.196

0 Comments Add a Comment?