Cotton Mather and the Salem Witch Trials

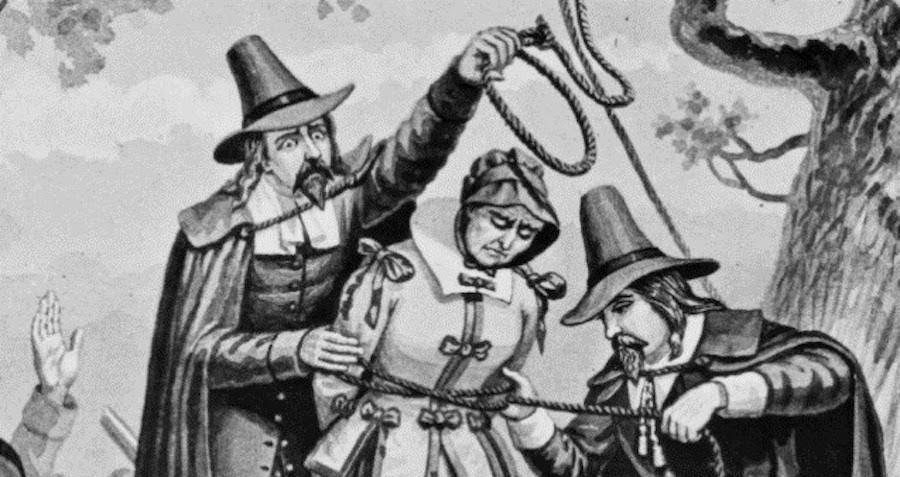

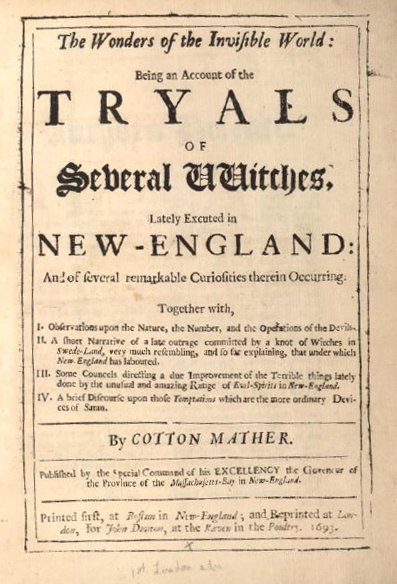

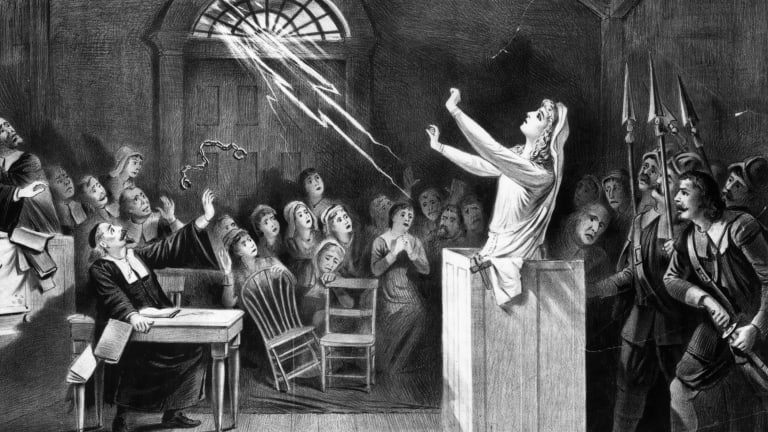

Fears of witchcraft and paranormal occurrences have been commonplace throughout history, with one of the most notorious spells of witch-hunting occurring in 1692 in Massachusetts. Twenty residents of Salem were tried and executed by the Court of Oyer and Terminer for indictments of witchcraft before the panic abated in 1693, and echoes of the tragedy still reverberate in the American memory today as shown by continuing interests and vast literatures on the subject. For this essay I shall be exploring an account of the trials written by Cotton Mather, an eminent Puritan minister who played an active role in the hysteria, in order to investigate what his explanation can reveal about the wider historical context of seventeenth-century New England. To begin with I shall explore Cotton Mather’s personal history and role in the trials since his inner conflicts, visible throughout Wonders of the Invisible World[1], are indicative of the later wider historical contexts I shall be investigating.

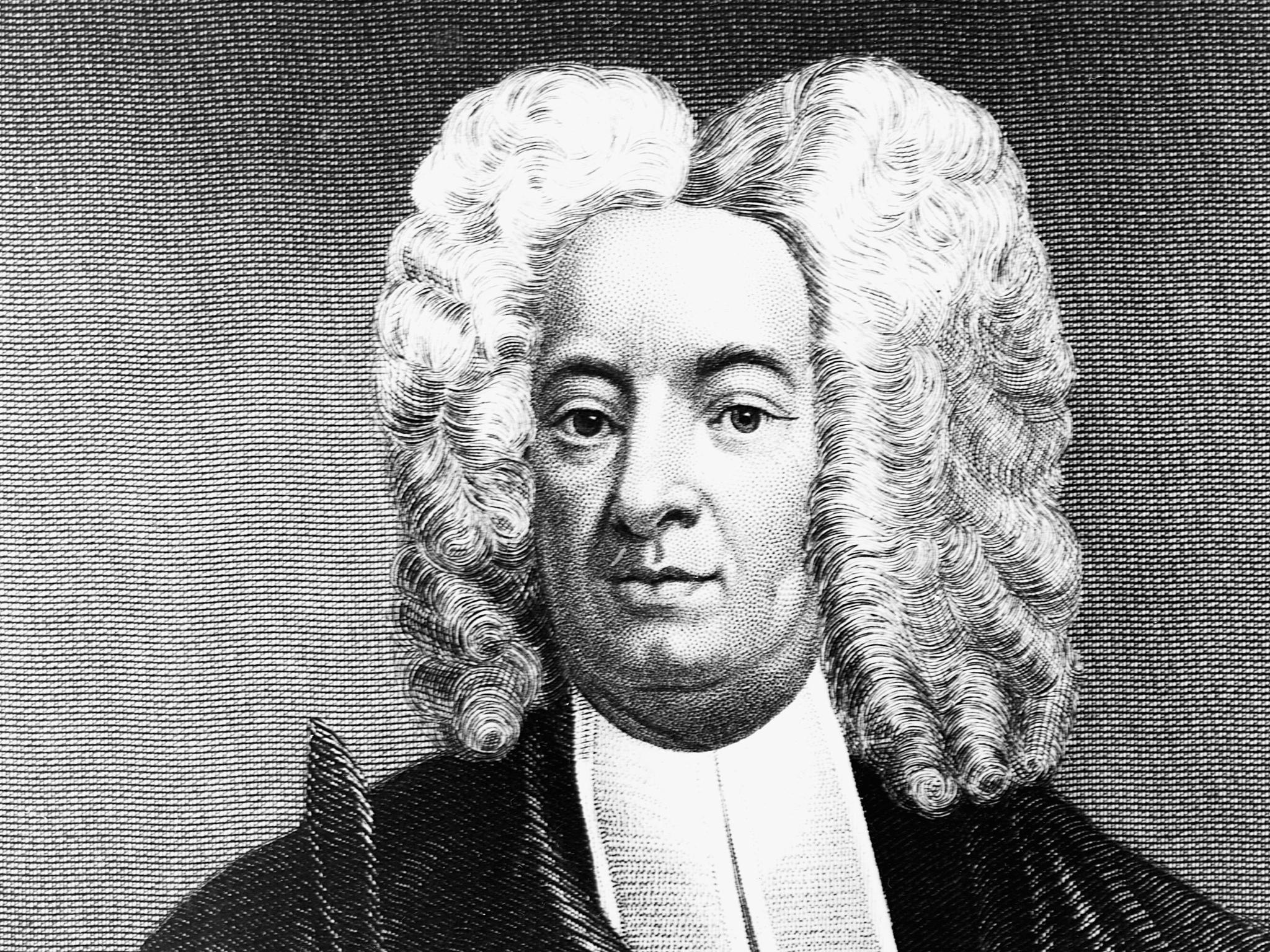

Cotton Mather was born into a prestigious family of honour, with both of his grandfathers possessing “moral and political authority” during the English Puritan migration to New England in the early seventeenth-century.[2] His father, Increase Mather, began studying at Harvard at the age of twelve and later became the president of Harvard College, after training to be ordained as a minister. Increase Mather was a highly religious man and prominent Puritan in Massachusetts, and Kenneth Silverman notes how he was a man “not easily pleased”.[3] Cotton Mather thus had a strained relationship with his father, and despite also graduating from Harvard and becoming the pastor of the Second Church of Boston he would arguably have felt the pressure of living in the shadow of his forefathers. Nevertheless, Cotton Mather was a renowned public figure in his own right; aside from being an inexhaustible writer producing over four hundred books and pamphlets, his reputation for “piety and redemptive action” gave him political, moral and religious influence in Boston.[4] He published Memorable Providences Relating to Witchcraft and Possession[5] in 1689 which detailed his rehabilitation of the afflicted Goodwin children during their supposed supernatural possession. This publication made Cotton Mather a key figure in the later Salem Witch Trials, as the local community turned to him “as the threat of witchcraft and the devil’s attention rose again on New England soil”.[6]

Kenneth Silverman states that in some form Mather’s contemporaries blamed him for the destructive events in Salem, for Mather “taught them to see cases of witchcraft”.[7] Robert Calef and Charles Wentworth Upham both agree that Cotton Mather rekindled the flames of the witch-hunt; “it was, indeed a superstitious age; but made much more so by [his] operations, influence, and writings”.[8] Mather played a role in setting up the witch-hunting Court of Oyer and Terminer, and was old friends with some of its lead actors including John Richards, Samuel Sewall and William Stoughton, who was notoriously the harshest prosecutor and strongest advocate for the reliability of spectral evidence. Cotton Mather, however, admitted in his diary that he “was always afraid of proceeding to convict and condemn any person […] upon so feeble an evidence, as a spectral representation”.[9] Cotton Mather sent a letter of caution to John Richards about the use of spectral evidence in convictions, claiming that it “lends itself to the accusation of people who have acted maliciously but not diabolically”[10] which would end up “ruining a poor neighbor so represented”.[11] However, Cotton Mather almost disregards his own criticisms at the end of the letter, urging the court to continue the trials, claiming that the “pains that are used for the tracing this witchcraft are to be thankfully accepted, and applauded among all this people of God”.[12] Robert Calef, an adversary and harsh critic of Cotton Mather, accused him of being “perfectly ambidexter, giving as great or greater encouragement to proceed in those dark methods, than cautions against them”.[13] This duality of thought that Mather possessed is partly the cause of his controversy and notoriety during the aftermath of the trials, as he condemned the use of spectral evidence whilst “continually remind[ing] his congregation of a hostile invisible world”.[14] Furthermore, he later defended the use of spectral evidence in Wonders, written in 1693, stating that “they have used […] spectral evidences, to introduce their further enquiries into the lives of the persons accused; […] the witch gang have been fairly executed”.[15] Cotton Mather and William Stoughton are the only perpetrators that did not publicly apologise for their roles after the trials. Increase Mather, who grew to oppose spectral evidence, and Governor William Phips played a part in disbanding the Court of Oyer and Terminer, though this is arguably due to the fact that Phips’ wife was one of the accused witches. Minister Samuel Parris, despite actively encouraging villagers to hunt and locate witches in his earlier sermons, read ‘Meditations for Peace’ to his congregation in 1694 apologising for his part in the trials. He admitted that spectral evidence was an unreliable cause for execution and claimed to have been “deluded by Satan […] for ‘God sometimes suffers the devil (as of late) to afflict in the shape not only innocent but pious persons’”.[16] Judge Samuel Sewall also regretted his role, stating in his diary that he was followed by God’s wrath after the trials as a result of his actions, pleading that he “cease visiting his sins upon him, his family, and upon the land”.[17] As Cotton Mather did not later condemn the use of spectral evidence, I argue that it was the wider social and political contexts that surrounded Mather at the time of his writing that led to the publication of such inconsistent ideas in his accounts of the trials.

The wider controversy that stemmed from Wonders is the result of Cotton Mather’s own conflicts and inner battles. Mather attempts to speak to different prospective audiences and has multiple intentions within his writing which sheds plentiful light on the wider context within which he was writing. The book ultimately acts as a defence of the witch trials; an attempt to convince the public to trust in the ‘justice’ of the court’s actions and Puritan ideals, as well as Mather’s way to “show the benefits and power of prayer on the afflicted and to convince New Englanders there was a very real threat from the invisible world”.[18] The events of the witch trials were noted and utilised by Mather to support his view that the devil had tried to infect the innocents of Salem, and endeavoured to convince his readers that New England was “going to overcome Satan’s attack and be an example to the rest of the world”.[19] In Mather’s own words he is writing “not as an advocate, but as an historian”, claiming to produce an unbiased account of the trials gathered from the official court records.[20]

In reality, Mather’s Wonders is anything but unbiased. Paul Wise questions the accuracy of his sources and concludes that “a reading of the trial records themselves would have given anyone, including Mather, a different impression than the one he gave to the world”.[21] Perhaps he hand-picked his sources to further his own argument, or had no choice but to use the sources that the governors selected for him. Either way, controversial cases where the accused plead their innocence were omitted from his analysis. Robert Calef criticises the propagandist nature of Mather’s book, claiming that Mather was commanded to write Wonders by William Phips “with not only the recommendation, but thanks, of the lieutenant governor”.[22] Mather may have been personally chosen by governmental officials to write as he was a well-known minister, thus he would have had a “wide audience as people sought to negotiate their fears and failings amidst unrest on, seemingly, every front—political, territorial, social, and spiritual”.[23] It could, therefore, be argued that Mather was harried into producing an account before the trials had officially ended with the aim of appeasing the angered populations. Calef’s view that Mather was appointed by the government is complimented by further evidence shown in a letter Mather wrote to William Stoughton, where he hopes his account will “vindicate the country, as well as the judges and the juries”.[24] As the judges presiding the convictions were family friends Mather must have felt loyalty to his superiors, especially considering that it was not within Puritan nature to defy authority. Any words of caution over the use of spectral evidence were outweighed by praise and self-subordination; he referred to himself as William Stoughton’s “sincere and most humble servant” and claimed that the “almighty God has employed Your Honour as His instrument for the extinguishing of as wonderful a piece of devilism as has been seen in the world”.[25] Whilst modern eyes may view his words and actions as controversial, “in Puritan New England he was doing his duty to his God and superiors”.[26] Furthermore, to implicate the judges for their heavy reliance on spectral evidence would provoke controversy and further anger the public. However, whilst there is evidence that Mather was condemned to write an account of the trials by the governors, other evidence shows that Mather wished himself into the position. He asked William Stoughton if he had permission to “give a distinct account of the trials” to “help very much to flatten that fury” that had befallen them.[27] On a personal level, writing on the trials may have benefited Mather; he could increase his audience as the topic of witchcraft held popular appeal, cement his “reputation as a divine” and live up to his lineage.[28] Nevertheless, whether Mather was compelled into writing or not, he had to agree to “defend the government, judges, and some of the ministers from the backlash against them that was occurring” despite the fact that he may have had differing views on the use of spectral evidence.[29]

Mather had the unfortunate task of trying to bring stability to a highly volatile Massachusetts, whose public was furious that the courts had executed twenty people and imprisoned hundreds of others with little to no evidence. However, such instability had also been rife preceding the witch trials, with many historians arguing that the political and religious unrest were the catalysts that sparked the trials. During the great migration to New England in the 1630s, Puritans sought religious freedoms from certain Catholic practices and believed that England had “strayed from the paths of righteousness […] the Lord had sought to preserve a saving remnant of His church by transferring it to an untainted refuge”.[30] Whilst they escaped religious persecution in England, the new colonies were still under English sovereignty and King James II attempted to tighten his control by unifying the colonies as one Dominion of New England in 1686. This new Dominion was set in place as a way to strengthen the colonies against ongoing Native American attacks, but more importantly it removed the local Puritan governments and replaced them with the English-appointed Edmund Andros, a member of the Church of England. By appointing Andros as the governor, James II “magnified the political and religious disconnection the colonists felt from their English rulers and offended many Puritan colonists”.[31] However the Glorious Revolution of 1688 filled the colonists with hope that James’s successor, the protestant William of Orange, would renounce the former king’s Dominion.[32] The colonists, including Cotton Mather, decided to expel Andros as the governor during the Boston Revolt of 1689, and in his place returned “to a godly government” by Puritan standards.[33] During the revolt Increase Mather campaigned for William Phips to be governor after the New Charter of 1691 was put in place. However, historian P. D. Swiney argues that “the Glorious Revolution served […] to undermine seriously the ties between England and her North American colonies”, which in turn undermined political authority in Massachusetts.[34] Without a strong political authority in place, the Puritans turned to their own moral authorities as an attempt to regain control of society, which thus allowed the Salem Witch Trials to unfold. In light of such wider context, Cotton Mather’s justification of the trials makes sense; by complying with the judges Mather was attempting to avoid “opposing a government for whose existence a revolt had been waged, and to open again the breach, only recently healed, between ministry and magistracy”.[35] Furthermore, William Phips was strongly endorsed by his own father, Increase Mather; Cotton Mather may have justified the events of Salem so as not to undermine his father’s campaign to make Phips the governor. His supposed support of the actions of the judges would thus “avoid King William’s ill favour over a possible public revolt that may have resulted in a new governor for the Massachusetts Bay colony”.[36]

Wonders was disseminated in England to show the King that the events of Salem were justified despite their controversy, and Cotton Mather noticeably acknowledges this English audience in his account as well as the intended American audience. The language he uses in the book presents us with an interesting context of a growing American identity away from England, and Mather’s own personal struggles with “the cognitive dissonance caused by the changing socio-political landscape of his community”.[37] Mather’s language at the beginning of the book illustrates his awareness of his different audiences – local, national and transnational – as he addresses them each individually. However, in the chapter ‘Enchantments Encountered’ Mather shifts his language, first referring to people in New England as “the people there”[38], almost as if he were writing from “the perspective of a loyal Englishman reporting home to England from abroad”.[39] From this he backtracks, referring to himself as part of the New England community through his use of ‘we’ and ‘our’, and further recognises America as its own separate entity by stating “America’s Fate surely must at the long run include New-England’s in it”.[40] Mather appears to identify with both an English and a separate American identity, which exemplifies the extreme political shifts that were occurring in the colonies before and during the witch trials.

Aside from the political contexts in which he was writing, Cotton Mather is also in the midst of changing religious contexts and increasing Puritan moral panic. While his initial intention in Wonders was to justify the trials, Mather also aimed to progress Puritan thought in an increasingly secular world. Thomas S. Kidd argues that “once the Glorious Revolution was embraced by New Englanders, their religious and political agenda had so fundamentally changed that it doesn’t make sense to call them Puritans any longer”.[41] Conflicts between the Catholic French and Protestant English placed the colonies in a vulnerable position with the threat of French territories in Canada, and many found a growing “sense of common cause with international Protestantism […] New Englanders shed many vestiges of their old Puritan identity in favour of a new identification with the Protestant interest”.[42] Cotton Mather must have noticed this shift in religious thought, and utilised his publication so as to reignite the Puritan fire. Puritan preachers tended to rationalise misfortune as retribution from God for the sins of the public, and employed extreme rhetoric when preaching their ideals. Cotton Mather utilises such language in his account, describing the witch trials as an “extraordinary Time of the Devils coming down in great Wrath upon us”.[43] There was a growing rift between religious conception and empiricism by the late seventeenth-century; despite Cotton Mather’s attempts to prove witchcraft as scientific fact, he only resulted in distorting “empirical design into alignment with his preconceptions” as opposed to altering his perceptions to the changing world around him.[44] Instead of uniting the public in favour of Puritanism, his book “united them against the Puritan authority structure he was supporting” as the public no longer trusted what he was attempting to preach.[45]

The strict Puritan lifestyle, from a modern perspective, has also been blamed for the accusations of the witch trials and Mather’s publication can help shed light on female repression and social persecution. Kenneth Silverman argues that the afflicted children in the Goodwin possession case were acting out against Puritan repression; “through their fits they acted out with impunity the worst fears of those ministers who denounced the rising generation for wanting to explore sex, taunt their parents and deride the ministry”.[46] Joseph Klaits agrees with this notion, claiming that the restrictive Puritan lifestyle made an “environment that was ripe for interpersonal conflict, depressive states and delusions” which “allowed these young women to unconsciously act out forbidden fantasies”.[47] Women held a precarious place within Puritan society as they were politically voiceless and held two functions in society; being a good wife and bearing children. Furthermore, the biblical story of Eve’s temptation to bite the devil’s apple was projected onto Puritan women. Just as Eve was “the original sinner”, Puritan women who disrupted their normal functionality were seen to have given into the devil’s temptation and were thus condemned as witches.[48] Cotton Mather notes in Wonders how the devil aimed to “seduce the souls, torment the bodies” and due to Puritan juxtapositions of femininity and sin women were seen to be the easiest targets of such seduction for their physical bodies were also weaker.[49] In a further publication Mather asserts his opinion of female weakness stating that “the Sex that is called, The Weaker Vessel, has not only a share with us, in the most of our Distempers, but also is liable to many that may be called, its Peculiar Weaknesses”.[50] Furthermore, George Bancroft notes how Mather described witches as being "among the poor, and vile, and ragged beggars upon Earth", which shows that accused witches were synonymous with typically ‘othered’ social groups.[51] The first women accused during the Salem Witch Trials all follow this pattern; Sarah Good was a beggar on the streets of Salem, Sarah Osbourne was an elderly woman who did not attend church regularly and Tituba was a west-Indian slave. Sarah Osborne’s lack of church attendance may have been seen as a renouncement of Christianity, despite her old age potentially making her infirm. Nevertheless, to renounce Christianity was to become “the devil’s servant, a partner in his universal war against all that was good”, so not attending church signified she had signed herself over to the devil.[52] As New England had been involved in frequent wars with Native Indian tribes, Tituba may have suffered further racial persecution during her trial. Cotton Mather drew heavy attention to Tituba’s racial identity during her trial, writing that “as the Witches call the Devil; and they generally say he resembles an Indian”.[53] Upon reaching the ‘New World’ the Puritans would have experienced racial difference for the first time as they descended from a predominantly white Europe. Mather concluded that “the New World had been the undisturbed realm of Satan”[54] before the Puritans made their arrival, so it would have been natural for a west Indian “Powawes”[55] to be the first accused of witchcraft during the trials.

In the words of Emerson Baker, the events of the Salem Witch Trials “offered a ‘perfect storm’, a unique convergence of conditions and events” that had never before been seen and carried catastrophic results, and Cotton Mather’s attempts to weather the aftermath demonstrate the volatility and extreme conflicts that occurred in his own mind.[56]

Mather’s uncertainties are prominent throughout Wonders, and it his own inner battles and distortion of evidence that allow us an insight into the context of colonial New England, from local and transnational political strife, the growing American identity, social persecution, Puritan repression and growing secularity as empirical thought began to take precedence. Mather was fully aware of the inaccuracy of spectral evidence but presented the judges with subtle cautions due to his staunch Puritan ideals; he did not wish to challenge his authority. Much later in his life Mather’s diary shows his regret over his role in Salem, as he did not appear “with Vigor enough to stop the proceedings of the Judges”.[57] Nevertheless, his complicity in 1693 is what ultimately led to his infamy; Cotton Mather has gone down in history as one of the most notorious witch-hunters of the Salem Witch Trials.

Further Reading:

Primary Sources

Burr, George Lincoln. “Letters of Governor Phips to the Home Government, 1692-1693.” Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases, 1648-1706. Accessed April 30, 2020. https://archive.is/20121212175912/http://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=BurNarr.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=3&division=div1#selection-11.0-11.78.

Calef, Robert. More Wonders of the Invisible World. London: Nath Hillar on London Bridge, 1700. https://www.academia.edu/39949790/Robert_Calef_More_wonders_of_the_invisible_world_or_The_wonders_of_the_invisible_world_displayed_1823.

Cooper, James F., and Kenneth P. Minkema (eds). The Sermon Notebook of Samuel Parris, 1689-1694. Boston: University Press of Virginia, 1993. https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/1188.

Glanvill, Joseph. Saducismus Triumphatus. London: S. Lownds, 1682. https://search-proquest-com.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/docview/2240953503?accountid=12117.

Mather, Cotton. Diary of Cotton Mather 1681-1708. Boston: The Society, 1911. https://archive.org/details/cu31924092202500.

Mather, Cotton. The Wonders of the Invisible World: Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches Lately Executed in New-England. London: John Russell Smith, 1862. https://archive.org/details/wondersinvisibl00mathgoog/page/n14/mode/2up.

Mather, Cotton. Memorable Providences: Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions. Boston: n.p., 1697. https://search-proquest-com.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/docview/2240849778?accountid=12117.

Mather, Increase. Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits. Boston: Benjamin Harris London Coffee-House, 1693. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/evans/N00531.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext.

Mather, Increase. Remarkable Providences: Illustrative of the Earlier Days of American Colonisation. London: Reeves and Turner, 1890. https://archive.org/details/remarkableprovid00mathuoft/page/n8/mode/2up.

Ray, Benjamin. “The Diary of Samuel Sewall, 1674-1729.” Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project (University of Virginia). Accessed April 30, 2020. http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/diaries/sewall_diary.html.

Ray, Benjamin. “To John Richards (May 31, 1692).” Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project (University of Virginia). Accessed April 30, 2020. http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/letters/to_richards1.html.

Ray, Benjamin. “To William Stoughton (September 2, 1692).” Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project (University of Virginia). Accessed April 30, 2020. http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/letters/to_stoughton.html.

Woodward, William Elliot. Records of Salem Witchcraft, Copied from the Original Documents. Roxbury: Private Printer for William E. Woodward, 1892. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=an0PAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP1.

Secondary Sources

Anderson, Allison R. “The Salem Witch Trials and the Political Chaos that Caused Them: How the Glorious Revolution Kindled the Fire of Colonial Unrest.” Dissertation, Western Illinois University, 2019.

Anderson, Virginia DeJohn. “Migrants and Motives: Religion and the Settlement of New England, 1630-1640.” The New England Quarterly 58, no. 3 (1985): 339-383.

Baker, Emerson. A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Bancroft, George. History of the Colonisation of the United States, Vol. 1. Boston: Little and Brown, 1843.

Boyer, Paul, and Stephen Nissenbaum. Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1974.

Breslaw, Elaine G. Witches of the Atlantic World: A Historical Reader and Primary Sourcebook. New York and London: New York University Press, 2000.

Evans, Laura A. “American Identity at a Crossroads: Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World.” Master of Arts dissertation, Oregon State University, 2012.

Fowler, Samuel Page. An Account of the Life and Character of the Rev. Samuel Parris, of Salem Village, and of His Connection with the Witchcraft Delusion of 1692. Salem: Ives and Pease, 1857.

Goodbeer, Richard. The Devil’s Dominion: Magic and Religion in Early New England. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Harley, David. “Explaining Salem: Calvinist Psychology and the Diagnosis of Possession.” The American Historical Review 101, no. 2 (1996): 307-330.

Jensen, Gary. The Path of the Devil: Early Modern Witch Hunts. Landham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007.

Kidd, Thomas S. “What Happened to the Puritans?” Historically Speaking 7, no. 1 (2005): 32-34.

Klaits, Joseph. Servants of Satan: The Age of the Witch Hunts. Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Lovejoy, David S. "Between Hell and Plum Island: Samuel Sewall and the Legacy of the Witches, 1692-97." The New England Quarterly 70, no. 3 (1997): 355-367.

Lovejoy, David S. The Glorious Revolution in America. New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1972.

Miller, Perry. The New England Mind: From Colony to Province. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1953.

Pomeroy, Frank. “The Colours of Witchcraft: Ideas of Race in the Puritan Theory of Witchcraft.” Honour Thesis, Texas State University, 2016.

Reis, Elizabeth. “The Devil, the Body, and the Feminine Soul in Puritan New England.” The Journal of American History 82, no. 1 (1995): 15-36.

Roach, Marilynne K. Six Women of Salem: The Untold Story of the Accused and Their Accusers in the Salem Witch Trials. Boston: Da Capo, 2013.

Rosen, Maggie. “A Feminist Perspective on the History of Women as Witches.” Dissenting Voices 6, no. 1 (2017): 21-31.

Rosenthal, Bernard. Salem Story: Reading the Witch Trials of 1692. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Silverman, Kenneth. The Life and Times of Cotton Mather. New York: Harper & Row, 1984.

Smith, Rebecca T. “Cotton Mather’s Involvement in the Salem Crisis.” The Spectrum: A Scholars Day Journal 2, no. 11 (2013): 1-21.

Smith Tucker, Veta. “Purloined Identity: The Racial Metamorphosis of Tituba of Salem Village.” Peer Reviewed Articles 1 (2000): 624-634.

Swiney, P. D. “Interpretive Essay.” In Events that Changed America through the Seventeenth Century, eds. John E. Findling and Frank W. Thackeray, 145-158. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Upham, Charles Wentworth. "Salem Witchcraft and Cotton Mather." The Historical Magazine and Notes and Queries Concerning the Antiquities, History and Biography of America Vol. 6, no. 3. New York: Henry B. Dawson, 1869. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=nrMTAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP7.

Weisman, Richard. Witchcraft, Magic, and Religion in Seventeenth Century Massachusetts. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1984.

White, Eugene Edmond. Puritan Rhetoric: The Issue of Emotion in Religion. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009.

Wise, Paul M. “Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World: An Authoritative edition.” Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2005.

References:

[1] Cotton Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World: Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches Lately Executed in New-England (London: John Russell Smith, 1862). https://archive.org/details/wondersinvisibl00mathgoog/page/n14/mode/2up. Henceforth, Wonders.

[2] Kenneth Silverman, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 4.

[3] Silverman, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather, 9.

[4] Laura A. Evans, “American Identity at a Crossroads: Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World” (Master of Arts dissertation, Oregon State University, 2012), 14.

[5] Cotton Mather, Memorable Providences: Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions (Boston: n.p., 1697). https://search-proquest-com.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/docview/2240849778?accountid=12117.

[6] Evans, “American Identity,” 14.

[7] Silverman, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather, 87.

[8] Charles Wentworth Upham, "Salem Witchcraft and Cotton Mather," The Historical Magazine and Notes and Queries Concerning the Antiquities, History and Biography of America Vol 6, no. 3. (New York: Henry B. Dawson, 1869), 140. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=nrMTAAAAYAAJ&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP7.

[9] Cotton Mather, Diary of Cotton Mather 1681-1708 (Boston: The Society, 1911), 150. https://archive.org/details/cu31924092202500.

[10] Silverman, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather, 98.

[11] Benjamin Ray, “To John Richards (May 31, 1692),” Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project (University of Virginia), accessed April 30, 2020. http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/letters/to_richards1.html.

[12] Ray, “To John Richards (May 31, 1692).”

[13] Robert Calef, More Wonders of the Invisible World (London: Nath Hillar on London Bridge, 1700), 152. https://www.academia.edu/39949790/Robert_Calef_More_wonders_of_the_invisible_world_or_The_wonders_of_the_invisible_world_displayed_1823.

[14] Silverman, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather, 88.

[15] Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World, 84.

[16] Emerson Baker, A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 231.

[17] David S. Lovejoy, "Between Hell and Plum Island: Samuel Sewall and the Legacy of the Witches, 1692-97," The New England Quarterly 70, no. 3 (1997): 360.

[18] Rebecca T. Smith, “Cotton Mather’s Involvement in the Salem Crisis,” The Spectrum: A Scholars Day Journal 2, no. 11 (2013): 20.

[19] Evans, “American Identity,” 15.

[20] Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World, 110.

[21] Paul M. Wise, “Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World: An Authoritative edition” (Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2005), 335.

[22] Calef, More Wonders of the Invisible World, 229.

[23] Evans, “American Identity,” 14.

[24] Benjamin Ray, “To William Stoughton (September 2, 1692),” Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project (University of Virginia), accessed April 30, 2020. http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/letters/to_stoughton.html.

[25] Ray, “To William Stoughton (September 2, 1692).”

[26] Smith, “Cotton Mather’s Involvement in the Salem Crisis,” 20.

[27] Ray, “To William Stoughton (September 2, 1692).”

[28] Wise, “Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World,” 326.

[29] Wise, “Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World,” 332.

[30] Virginia DeJohn Anderson, “Migrants and Motives: Religion and the Settlement of New England, 1630-1640,” The New England Quarterly 58, no. 3 (1985): 341.

[31] Allison R. Anderson, “The Salem Witch Trials and the Political Chaos that Caused Them: How the Glorious Revolution Kindled the Fire of Colonial Unrest,” (Dissertation, Western Illinois University, 2019), 8.

[32] Lovejoy, The Glorious Revolution in America, 235.

[33] Ibid.

[34] P.D. Swiney, “Interpretive Essay,” in Events that Changed America through the Seventeenth Century, ed. John E. Findling and Frank W. Thackeray (Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000), 154.

[35] Silverman, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather, 102.

[36] Wise, “Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World,” 335.

[37] Evans, “American Identity,” 39.

[38] Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World, 9.

[39] Evans, “American Identity,” 46.

[40] Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World, 76.

[41] Thomas S. Kidd, “What Happened to the Puritans?” Historically Speaking 7, no. 1 (2005): 32.

[42] Thomas S. Kidd, “What Happened to the Puritans?” Historically Speaking 7, no. 1 (2005): 32.

[43] Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World, 3.

[44] Wise, “Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World,” 327.

[45] Evans, “American Identity,” 39.

[46] Silverman, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather, 90.

[47] Joseph Klaits, Servants of Satan: The Age of the Witch Hunts (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1987), 125.

[48] Maggie Rosen, “A Feminist Perspective on the History of Women as Witches,” Dissenting Voices 6, no. 1 (2017): 23.

[49] Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World, 80.

[50] Elizabeth Reis, “The Devil, the Body, and the Feminine Soul in Puritan New England,” The Journal of American History 82, no. 1 (1995): 27.

[51] George Bancroft, History of the Colonisation of the United States, Vol. 1 (Boston: Little and Brown, 1843), 85.

[52] Klaits, Servants of Satan, 2.

[53] Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World, 126.

[54] Frank Pomeroy, “The Colours of Witchcraft: Ideas of Race in the Puritan Theory of Witchcraft” (Honour Thesis, Texas State University, 2016), 1.

[55] Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World, 74.

[56] Baker, A Storm of Witchcraft, 6.

[57] Perry Miller, The New England Mind: From Colony to Province (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1953), 206.

0 Comments Add a Comment?