Feminism and Emotions within the 'Riot Grrrl' Movement

The ‘riot grrrl’ movement stemmed from the original punk movement of the 1970s and was most prominent in the 1990s, being credited by some to have stimulated third-wave feminism as they aimed to fight sexism, patriarchy and misogyny. The original punk movement began in the 1970s as a retaliation to the political and socio-economic climate of Britain and America, and resulted in a “distinct youth culture that in turn provoked a media-driven moral panic and prompted notable cultural change”. The punk movement compliments feminist theories as it was seen as a revolt against social and cultural norms in society, and “offered the basis for an alternative lifestyle beyond the perceived mainstream”. However, punk was a highly male dominated sphere and the women who wished to be able to express themselves musically, challenge notions of femininity, express anger at society and bend gender boundaries found no space for themselves within the movement. Referring to Barbara Rosenwein’s research into the history of emotions, women did not find an emotional community in punk so they fashioned their own in the form of ‘riot grrrl’. If society was the emotional regime enforcing dominant emotional and gender norms upon women, ‘riot grrrl’ became their emotional refuge and shelter from oppression. Anna Batt describes ‘riot grrrls’ as ones to “spit in the face of the patriarchy, making them leaders for future women, but deviant in society and in media”.

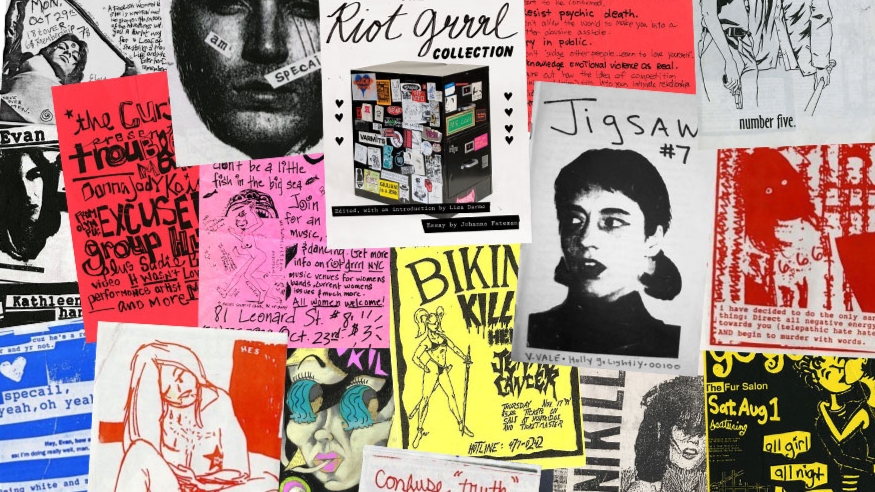

Aside from the actual music produced, emotional shelters were found in self-produced magazines, or ‘fanzines’, which were used as a form of networking that addressed feminist issues, promoted poetry and art and published information about performances. Through their fanzines and music, ‘riot grrrls’ addressed topics that were typically taboo in society, like abortion, sexual pleasure, rape and lesbianism, whilst provoking younger girls to explore their own political identities and resist against ‘the man’; this elicited a severe reaction from the general public. Some of the negative reaction to the movement revolved around the anger and violence they enabled in their shows, as “the idea of women and violence is often communicated through feelings […] of confusion, shock, pity, or unease about legitimizing/normalizing women’s agency”. The moral panic that ensued was an emotional reaction to such a “disruptive moment with regards to gendered social norms”, and culminated in intense media scrutiny where caricatures were created out of band members. This formation of caricatures, as well as intense criticisms for the masculine appearance of the ‘riot grrrls’, proves that their messages were not taken seriously and their activism and ideals were discredited, similar to how the suffragettes were treated throughout the first-wave feminist movement. The emotional anger of women in punk was received with further anger and outrage from the public, thus demonstrating how subcultures and the mainstream emotionally stimulated and clashed with each other.

Whilst such disparaging media activity was also present in feminist activism, there is some conflict with feminist theory and the ‘riot grrrl’ movement. Second-wave feminist theorists of the 1960s and 1970s did not believe that female punk groups supported feminist ideals, claiming that “the movement exhorted promiscuity in the disguise of sexual freedom”. Some third-wave feminists agreed with this notion, adding that ‘riot grrrls’ were “naïve, ignorant and obnoxious” and had “distorted the feminist slogan”, but the bands interpreted these critiques as being similar to the moral panic that was demonstrated in the media. This division between ‘riot grrrls’ and feminist theorists is contradictory, as the punk bands had emanated from the feminist movement who later condemned them. The ‘riot grrrls’ acted as a “deviation from the politicised protests, such as marches and petitions, of second-wave feminism” which proposed an alternative way of “conceptualising feminism based on subversions of cultural activism”. The musicians further seemed to deviate from third-wave feminism; whilst third-wave feminist theorists began to move away from women’s studies to focus on gender as a concept, ‘riot grrrls’ maintained their focus on women. This focus on women mirrors issues present in feminist theory, whereby neglecting to involve men and focus on gender as a concept becomes too exclusive to be effective as a form of activism, and too radical to elicit a positive response from the media. Despite ‘riot grrrl’ not seeming inclusive, the movement was profoundly active in including women from all different cultures, sexualities and ages, with the exclusion of men meaning that they could pour all of their focus on women.

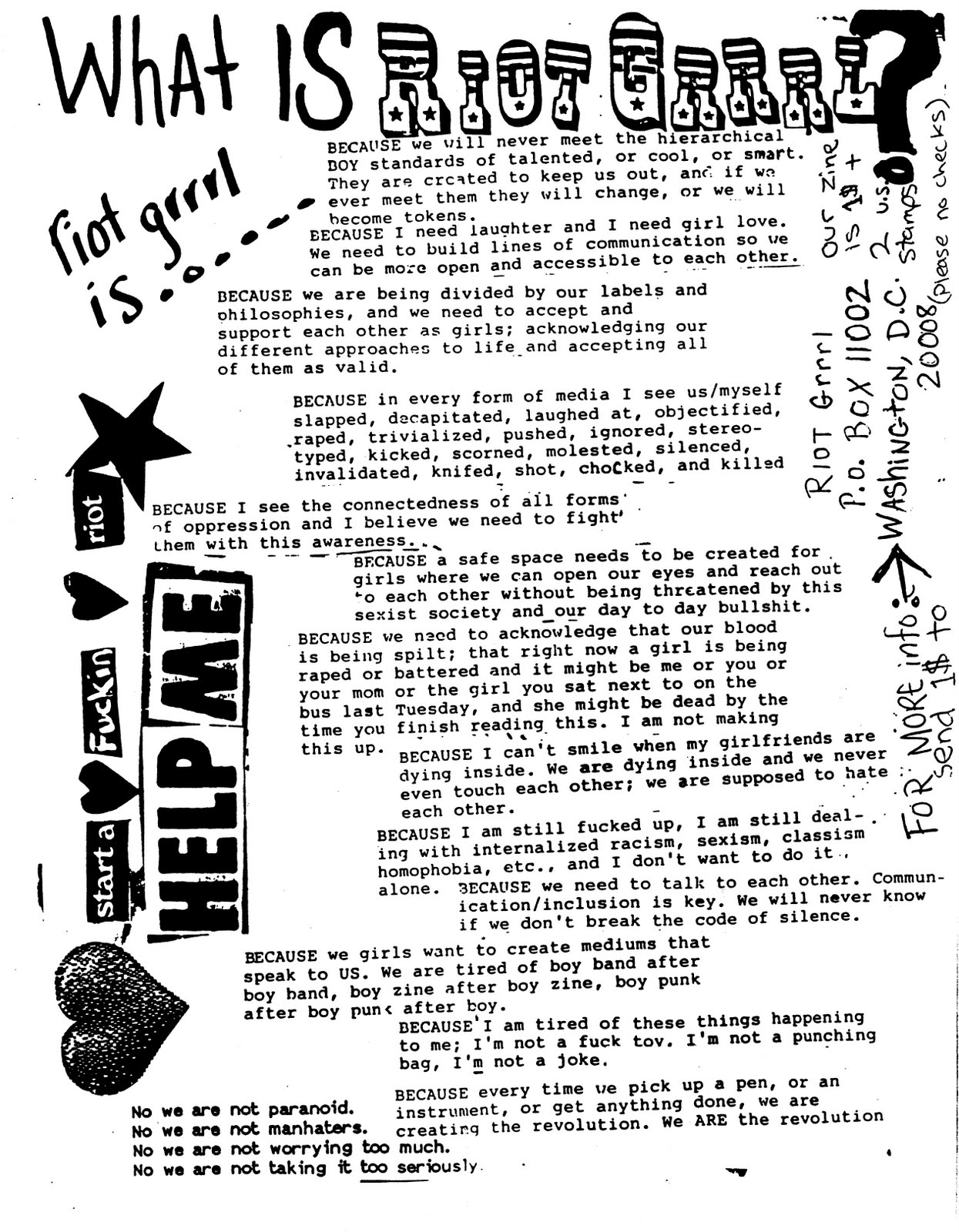

Kathleen Hanna’s ‘Riot Grrrl’ Manifesto

“Because we will never meet the hierarchal boy standards of talented, or cool, or smart. They are created to keep us out, and if we ever meet them they will change, or we will become tokens. Because I need laughter and I need girl love. We need to build lines of communication so we can be more open and accessible to each other. Because we are being divided by our labels and philosophies, and we need to accept and support each other as girls; acknowledging our different approaches to life and accepting them all as valid. Because in every form of media I see us/myself slapped, decapitated, laughed at, objectified, raped, trivialised, pushed, ignored, stereotyped, kicked, scorned, molested, silenced, invalidated, knifed, shot, chocked and killed. […] Because a safe space needs to be created for girls where we can open our eyes and reach out to each other without being threatened by this sexist society and our day to day bullshit. Because we need to acknowledge that our blood is being spilt; that right now a girl is being raped or battered and it might be me or you or your mom or the girl you sat next to on the bus last Tuesday, and she might be dead by the time you finish reading this. I am not making this up. […] Because I am still fucked up, I am still dealing with internalised racism, sexism, classism, homophobia etc., and I don’t want to do it alone. Because we need to talk to each other. Communication/inclusion is key. We will never know if we don’t break the code of silence. Because we girls want to create mediums that speak to us. We are tired of boy band after boy band, boy zine after boy zine, boy punk after boy punk after boy. Because I am tired of these things happening to me; I’m not a punching bag, I’m not a joke. Because every time we pick up a pen, or an instrument, or get anything done, we are creating the revolution. We ARE the revolution”.

In this quote Kathleen Hanna notes how men are held to a different standard to women, which in turn acts as a way of excluding women from the male-centric ways of the punk music scene. This issue has always been present in feminist theory; the formation of the scholarship rose from a need to destabilise the male-centred histories that had previously been written, giving women agency in history for the first time. Female agency in a world that struggles to keep it subdued is a central and continuing concept of feminist theory, and because of feminist activism it is believed that women have now gained the agency they desired. However, the fact that Kathleen Hanna notes that women are still excluded from many social circles because of their gender shows that female agency is still an important issue in our contemporary world. Hanna’s expression of a need for more ‘girl love’, as well as her want for better communication between women and safe spaces to escape from sexism within society, complements the approaches of theorists of the history of emotions. She is craving an emotional community of women within the ‘riot grrrl’ movement, which corresponds to the research of Barbara Rosenwein. The approaches of William Reddy can also be utilised in this aspect; sexism within society is the emotional regime that Hanna wishes to break from, the source of the enforcement of traditional gender roles, and the ‘riot grrrl’ movement is her safe space, or emotional refuge, where she can take shelter and express her freedom from the regime of conventional femininity. Whilst not conforming to classic ideas of either the public or the private realm, girls created fanzines where they could “operate as a private place legitimately able to exclude both adults and young men”. In the source she notes how women are divided by their philosophies and labels and need to accept and support each other as women in an increasingly hostile environment.

Approaches to inclusivity have been fervently explored by feminist theorists, as second-wave feminist scholarship was notoriously riddled with the internalised racism, classism and homophobia that Hanna disparages. As a feminist herself, Hanna was undoubtedly aware of the white-centric feminism displayed in the second-wave movement and may have been attempting to play a part in diversifying the movement as it began to enter its third-wave. She further states how women are being continuously violated and facing extreme forms of violence from men, as a way to possibly stimulate a reaction of fear and anger from her audience. This could be due to the fact that the only way to overcome such an obstacle in society is to surround it with an emotional energy of anger and fear, the two emotions which have historically stimulated the most social change. Throughout the source Hanna portrays the approach that the emotional standards of women have changed, and that it is time to mobilise and act on their anger in order to start a revolution. Kathleen Hanna wrote the ‘Riot Grrrl Manifesto’ in her fanzine in 1991, a time when “the cultural fascination with girlhood” was juxtaposed with the regulation of their “bodies, labour and behaviour”. The notion of girl power was on the rise as a “provocative mix of youth, vitality, sexuality and self-determination”; yet girls struggled for power over their own identities, as well as their ability to re-invent themselves, and this contrast between repression and self-expression was articulated through self-published fanzines. Bikini Kill acted as a political medium for girls as well as a cultural artefact, and “provided an alternative to the politically correct women’s magazines, and […] revealed interests in exploring non-traditional forms of young female identity”. Furthermore, the fanzines, sometimes referred to as ‘angry grrrl zines’, “became a key site for women and girls to discuss, examine and resist the cultural devaluation of women with each other in a safe space”. Kathleen Hanna was able to undermine, toy with and question the dominant archetypes of girlhood without a care for what others thought, which inevitably led to a new generation of women who were keen to question and contest the societies that they inhabited.

From music to fanzines, the ‘riot grrrl’ punk subculture allowed women to “explore gender boundaries, to investigate their own power, anger, aggression – even nastiness”, and this was a visible threat to mainstream society. Punk women destroyed “the established image of femininity” through their creation of emotionally charged music and facilitation of anger, an “emotion considered to be particularly socially dangerous, threatening and intolerable for women to display”. As displayed throughout feminist theory, ‘riot grrrls’ continuously fought to better themselves within society at the risk of being seen as immoral by that society. However, whilst feminist historians applied their own activism to the past, female punks took their activism and projected it into their music and onto the future. Janey Starling, from contemporary female punk group Dream Nails, notes that the punk feminist movement has not changed since its birth, as she states that “it’s come from a place where women are saying ‘fuck it’ because the stakes are so high […] I’ve got all this rage that I need to let out or I’m going to explode”. This statement shows that even today, the punk rock movement has facilitated and created spaces for women to both express their anger and emotions whilst conducting feminist activism to attempt to further women’s positions within society.

Further Reading

Åhäll, Linda. “Affect as Methodology: Feminism and the Politics of Emotion.” International Political Sociology 12 (2018): 36-52.

Batt, Anna. “Bubblegum Girls Need Not Apply: Deviant Women the Punk Scene.” On Our Terms: The Undergraduate Journal of the Athena Centre for Leadership Studies at Barnard College 2, no. 1 (2014): 52-62.

Bennett, Judith. History Matters: Patriarchy and the Challenge of Feminism. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Boddice, Rob. The History of Emotions. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018.

Downes, Julia. “Riot Grrrl: The Legacy and Contemporary Landscape of DIY Feminist Cultural Activism” (2007): 9-38.

Downes, Julia. “The Expansion of Punk Rock: Riot Grrrl Challenges to Gender Power Relations in British Indie Music Subcultures.” Women’s Studies 41 (2012): 204-237.

Dyhouse, Carol. Girl Trouble: Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2014.

Hanna, Kathleen. “Riot Grrrl Manifesto.” Bikini Kill Zine 2, 1991. https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/riotgrrrlmanifesto.html.

Harris, Anita. “gURL Scenes and Grrrl Zines: The Regulation and Resistance of Girls in Late Modernity.” Feminist Review no. 75 (2003): 38-56.

Hercus, Cheryl. “Identity, Emotion and Feminist Collective Action.” Gender and Society 13, no. 1 (1999): 34-55.

Lutz, Catherine. “Emotions and Feminist Theories.” In Gender Feelings, edited by Daniela Rippl and Verena Mayer, 104-121. Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2008.

Mantila, Susanna. “Ugly Girls on Stage: Riot Grrrl Reflected through Misrepresentations.” Master’s Thesis, University of Vaasa, 2009.

Matt, Susan J. “Recovering the Invisible: Methods for the Historical Study of the Emotions.” In Doing Emotions History, edited by Peter N. Stearns and Susan J. Matt, 41-53. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Mohdin, Aamna. “’I’ve got all this rage’: the feminist punk groups demanding to be heard”. The Guardian, April 12, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/apr/12/ive-got-all-this-rage-the-feminist-punk-groups-demanding-to-be-heard [accessed 15/12/19].

Morgan, Sue. “Theorising Feminist History: A Thirty-Year Retrospective.” Women’s History Review 18, no. 3 (July 2009): 381-407.

Plamper, Jan. The History of Emotions: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Reddy, William M. “Against Constructionism: The Historical Ethnography of Emotions.” Current Anthropology 38, no. 3 (1997): 327-351.

Rosenwein, Barbara H. “Problems and Methods in the History of Emotions.” Passions in Context: International Journal for the History and Theory of Emotions 2 (2011): 1-32.

Scheer, Monique. “Are Emotions a Kind of Practice (And Is That What Makes Them Have a History)? A Bourdieuian Approach to Understanding Emotion.” History and Theory 51 (2012): 193-220.

Scott, Joan W. “Back to the Future.” Review of History Matters: Patriarchy and the Challenge of Feminism, by Judith Bennett. History and Theory 47 (May 2008): 279-284.

Stearns, Peter N., and Carol Z. Stearns. “Emotionology: Clarifying the History of Emotions and Emotional Standards.” The American Historical Review 90, no. 4 (1985): 813-836.

Stearns, Peter N., and Matt, Susan J., ed. Doing Emotions History. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Worley, Matthew. “Punk, Politics and Youth Culture, 1976-1984.” Reading History. https://unireadinghistory.com/punk-politics-and-youth-culture/ [accessed 15/12/19].

Zemon Davis, Natalie. “‘Women’s History’ in Transition: The European Case.” Feminist Studies 3, no. 3-4 (1976): 83-103.

0 Comments Add a Comment?